- Etymology

- Taxonomy

- Gallery

- Contact Us

Taxonomy:

In 1758, the Swedish botanist and zoologist Carl Linnaeus published in his Systema Naturae the binomial nomenclature. Canis is the Latin word meaning "dog", and under this genus he listed the doglike carnivores including domestic dogs, wolves, and jackals. He classified the domestic dog as Canis familiaris, and the wolf as Canis lupus. Linnaeus considered the dog to be a separate species from the wolf because of its "cauda recurvata" (upturning tail) which is not found in any other canid.

Subspecies:

In the third edition of Mammal Species of the World published in 2005, the mammalogist W. Christopher Wozencraft listed under C. lupus 36 wild subspecies, and proposed two additional subspecies: familiaris (Linnaeus, 1758) and dingo (Meyer, 1793). Wozencraft included hallstromi—the New Guinea singing dog—as a taxonomic synonym for the dingo. Wozencraft referred to a 1999 mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) study as one of the guides in forming his decision, and listed the 38 subspecies of C. lupus under the biological common name of "wolf", the nominate subspecies being the Eurasian wolf (C. l. lupus) based on the type specimen that Linnaeus studied in Sweden. Studies using paleogenomic techniques reveal that the modern wolf and the dog are sister taxa, as modern wolves are not closely related to the population of wolves that was first domesticated. In 2019, a workshop hosted by the IUCN/Species Survival Commission's Canid Specialist Group considered the New Guinea singing dog and the dingo to be feral Canis familiaris, and therefore should not be assessed for the IUCN Red List.

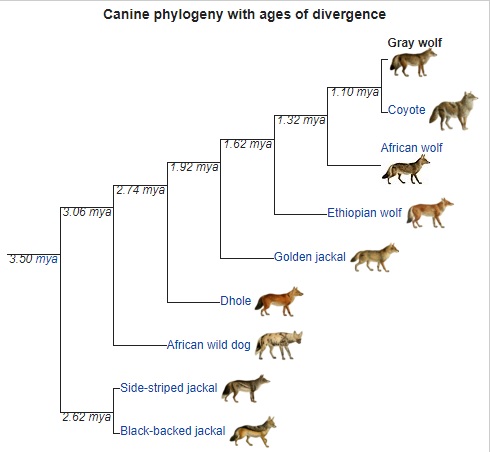

Evolution:

The phylogenetic descent of the extant wolf C. lupus from C. etruscus through C. mosbachensis is widely accepted. The earliest fossils of C. lupus were found in what was once eastern Beringia at Old Crow, Yukon, Canada, and at Cripple Creek Sump, Fairbanks, Alaska. The age is not agreed upon but could date to one million years ago. Considerable morphological diversity existed among wolves by the Late Pleistocene. They had more robust skulls and teeth than modern wolves, often with a shortened snout, a pronounced development of the temporalis muscle, and robust premolars. It is proposed that these features were specialized adaptations for the processing of carcass and bone associated with the hunting and scavenging of Pleistocene megafauna. Compared with modern wolves, some Pleistocene wolves showed an increase in tooth breakage similar to that seen in the extinct dire wolf. This suggests they either often processed carcasses, or that they competed with other carnivores and needed to consume their prey quickly. Compared with those found in the modern spotted hyena, the frequency and location of tooth fractures in these wolves indicates they were habitual bone crackers.

Genomic studies suggest modern wolves and dogs descend from a common ancestral wolf population that existed 20,000 years ago. A 2021 study found that the Himalayan wolf and the Indian plains wolf are part of a lineage that is basal to other wolves and split from them 200,000 years ago. Other wolves appear to have originated in Beringia in an expansion that was driven by the huge ecological changes during the close of the Late Pleistocene. A study in 2016 indicates that a population bottleneck was followed by a rapid radiation from an ancestral population at a time during, or just after, the Last Glacial Maximum. This implies the original morphologically diverse wolf populations were out-competed and replaced by more modern wolves.